LLM Inference Optimization

You’re not an ML Engineer if you can’t deploy and optimize inference. This statement might sound harsh, but it reflects a fundamental shift in what the industry expects from machine learning practitioners today. Building impressive models in research environments is one thing; keeping them running efficiently in production under real-world constraints is an entirely different challenge.

Large transformer models have become the backbone of modern AI applications, delivering state-of-the-art results across numerous tasks. However, their power comes at a significant cost. The computational and memory requirements for inference can be prohibitive, with some models requiring multiple high-end GPUs and generating response times measured in seconds rather than milliseconds.

When your model hits production and users start complaining about 7-second latencies while your GPU utilization sits at 99% and costs spiral out of control, the gap between research and production becomes painfully clear.

The challenge isn’t just about making models work; it’s about making them work efficiently at scale. Modern production environments demand systems that can handle thousands of concurrent requests, maintain sub-second response times, and operate within reasonable cost budgets. This requires a deep understanding of inference optimization techniques that go far beyond basic model compression or quantization.

Key-Value Caching with Paged Attention

The transformer architecture’s self-attention mechanism creates a fundamental computational bottleneck during inference. By default, when generating each new token, the model recomputes attention weights over the entire sequence history. For a sequence of length \(n\), this results in \(O(n^2)\) computational complexity that grows quadratically with context length. This becomes particularly problematic for applications requiring long context windows, such as document analysis or extended conversations.

In practice, this bottleneck manifests differently depending on your hardware setup. On a single A100 with 80GB memory, you might handle 32K context length with batch size 1, but try to increase the batch size to 4 and you’ll immediately hit out-of-memory errors. The memory consumption follows the pattern:

\[\text{Memory} = \text{batch\_size} \times \text{seq\_length} \times \text{hidden\_size} \times \text{num\_layers} \times 2 \times \text{precision\_bytes}\]where the factor of 2 accounts for both keys and values.

Key-Value (KV) caching addresses this inefficiency by storing the computed key and value matrices from previous tokens, allowing the model to only compute attention for the new token against the cached states. The attention computation becomes:

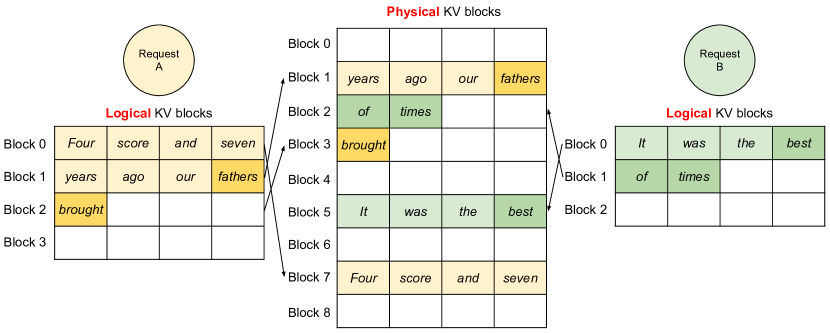

\[\text{Attention}(Q_{\text{new}}, K_{\text{cached}}, V_{\text{cached}}) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{Q_{\text{new}} K_{\text{cached}}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V_{\text{cached}}\]However, naive KV caching implementations create their own problems. A typical production scenario involves serving hundreds of concurrent users with varying conversation lengths. Without proper memory management, you’ll see memory fragmentation where 40GB of your 80GB GPU memory shows as “allocated” but only 20GB is actually being used for active computations. The remaining 20GB is trapped in unusable fragments between completed conversations.

This fragmentation issue becomes particularly acute during peak usage periods. You might start the day serving 200 concurrent users smoothly, but by afternoon, after thousands of conversations have started and completed, you can only handle 100 concurrent users due to fragmented memory. The only solution is often a complete service restart, which is unacceptable in production environments.

Paged attention, implemented in systems like vLLM, revolutionizes KV cache management by treating memory like an operating system manages virtual memory. Instead of allocating contiguous memory blocks for each sequence, paged attention divides the KV cache into fixed-size pages that can be dynamically allocated and deallocated. In practice, this means using page sizes of 16 or 32 tokens, creating a balance between memory efficiency and computational overhead.

The real-world impact is dramatic. In production deployments, paged attention can improve memory utilization from 60-70% to 90-95%, allowing you to serve 2-3x more concurrent users on the same hardware. The page table overhead is minimal, typically consuming less than 1% of total memory, while the flexibility gains are substantial. When a user ends their conversation, their memory pages are immediately available for new conversations, eliminating the gradual memory fragmentation that plagues traditional implementations.

Continuous Batching for Dynamic Workloads

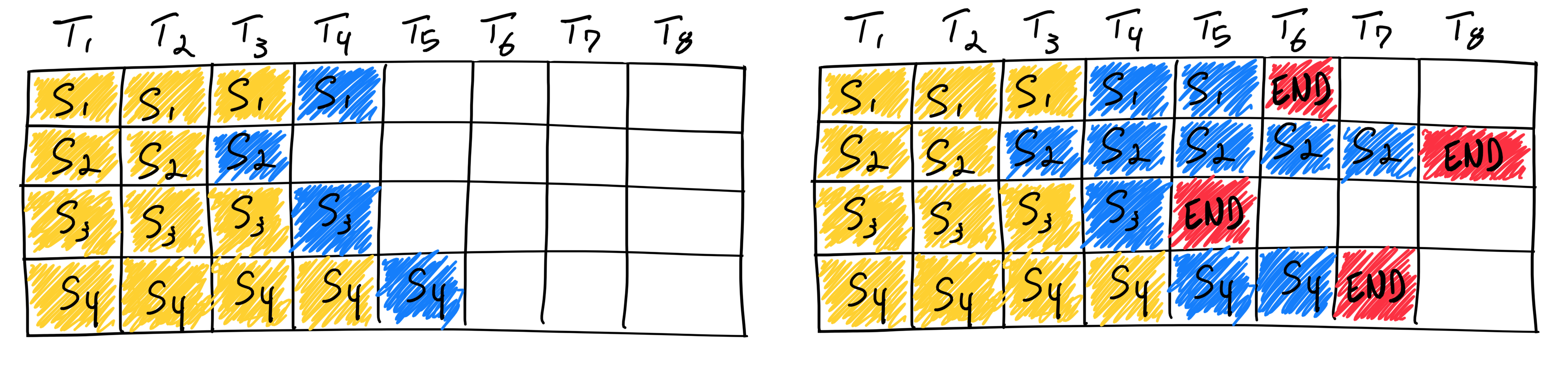

Traditional batching approaches assume that requests arrive in synchronized groups, but production workloads are inherently streaming and asynchronous. Users don’t coordinate their requests, leading to irregular arrival patterns that can severely underutilize available compute resources if handled naively.

The reality of production traffic is far messier than research benchmarks suggest. During typical business hours, you might see 50 requests per minute with response lengths varying from 10 tokens to 2000 tokens. Traditional static batching with a batch size of 8 would either waste GPU cycles waiting for enough requests to fill a batch, or force you to use smaller batch sizes that underutilize the hardware. The utilization often drops to 30-40% during off-peak hours when requests are sparse.

Continuous batching solves this problem by dynamically combining requests as they arrive, creating batches on-the-fly rather than waiting for predetermined batch sizes. The system maintains a queue of pending requests and continuously forms new batches based on available computational capacity and memory constraints.

The implementation complexity is significant. You need to track not just the current batch composition, but also predict memory requirements for each request addition. A naive approach might add requests to a batch until GPU memory is exhausted, but this leads to out-of-memory crashes when the prediction is wrong. A more robust approach maintains a safety margin of 10-15% and uses conservative estimates for memory consumption.

The key insight is that different requests within a batch can be at different stages of generation. While one request might be generating its 50th token, another could be starting its first. The system tracks the state of each request independently while still benefiting from the computational efficiency of batched operations. This requires sophisticated tensor manipulation where each row in the batch might have different sequence lengths and different remaining generation requirements.

In practice, continuous batching introduces latency tradeoffs that must be carefully managed. A request that arrives when the GPU is processing a large batch might wait 200-500ms before being included in the next batch. For interactive applications, this delay can be noticeable. Advanced implementations use preemption strategies where long-running requests can be temporarily paused to accommodate new, potentially shorter requests.

The scheduling algorithm becomes the critical component. A simple first-come-first-served approach can lead to head-of-line blocking where a single long request delays many shorter ones. Production systems typically implement weighted fair queuing or shortest-job-first strategies, but these require accurate prediction of request completion times, which is challenging for generative models where output length isn’t known in advance.

Real-world measurements show that continuous batching can achieve throughput improvements of 3-5x compared to traditional static batching in production environments with variable request patterns. However, the improvement depends heavily on request size distribution and arrival patterns. Workloads with many short requests see larger benefits than those dominated by long document processing tasks.

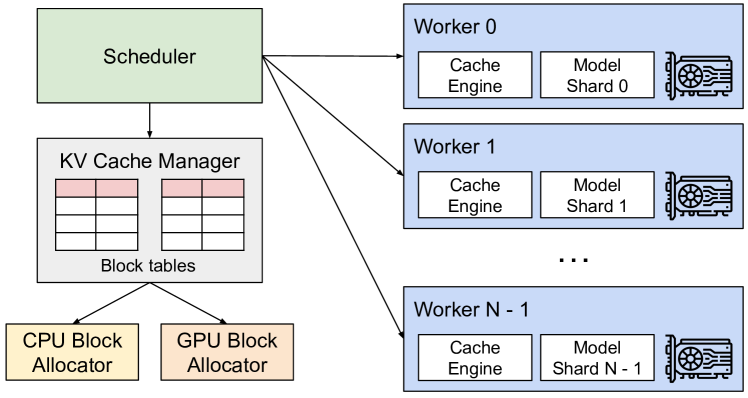

Multi-GPU Orchestration and Model Sharding

As models grow beyond the memory capacity of single GPUs, sophisticated distribution strategies become essential. Modern large language models often require multiple GPUs working in coordination, either through model parallelism (splitting the model across devices) or through replica serving (running multiple copies for higher throughput).

The transition from single-GPU to multi-GPU serving introduces a host of practical challenges that aren’t immediately obvious. A 70B parameter model like Llama-2-70B requires approximately 140GB of memory in FP16 precision, necessitating distribution across at least two A100 GPUs. However, simply splitting the model layers across GPUs introduces significant communication overhead that can reduce effective throughput by 40-60% compared to theoretical maximum.

Model parallelism involves partitioning the model’s layers or parameters across multiple GPUs. For transformer models, this typically means distributing attention heads across devices or splitting the feed-forward network components. The challenge lies in minimizing communication overhead between GPUs while maintaining computational efficiency.

In practice, tensor parallelism often works better than pipeline parallelism for transformer models. With tensor parallelism, each attention head computation \(\text{head}_i = \text{Attention}(Q_i, K_i, V_i)\) is distributed across GPUs, where each GPU handles a subset of heads. This requires all-gather operations after each layer, but the communication pattern is more predictable and the memory usage is more balanced.

Pipeline parallelism, where different layers run on different GPUs, seems attractive but introduces bubble time where GPUs wait for data from previous stages. In production, pipeline parallelism works well only with large batch sizes (32 or higher) that can keep all pipeline stages busy. For interactive workloads with small batch sizes, the pipeline bubbles can waste 50-70% of GPU cycles.

The networking infrastructure becomes critical for multi-GPU deployments. NVLink connections between GPUs on the same node provide 50-100 GB/s bandwidth, but inter-node communication over InfiniBand typically provides only 25-50 GB/s. This bandwidth difference means that placing communicating model components on the same node is crucial for performance.

Effective multi-GPU serving also requires intelligent request routing that considers the current load on each device, the memory requirements of incoming requests, and the communication costs of different placement strategies. Advanced systems can dynamically migrate requests between GPUs or adjust the parallelization strategy based on real-time performance metrics.

In production environments, GPU failures are not uncommon. A single GPU failure in a tensor-parallel setup brings down the entire model instance. Robust systems implement health monitoring that can detect GPU degradation before complete failure and gracefully migrate workloads to healthy replicas. The mean time to recovery (MTTR) for GPU failures can be 5-15 minutes, during which alternative serving capacity must handle the load.

Load balancing across GPU replicas requires more sophistication than traditional web service load balancing. GPU warmup time after a cold start can be 30-120 seconds depending on model size, and the memory state of each replica affects its capacity to accept new requests. Simple round-robin load balancing often leads to uneven utilization where some GPUs are overwhelmed while others are underutilized.

Token Streaming and Progressive Response Generation

User experience in interactive applications depends heavily on perceived responsiveness rather than just raw throughput. Even if generating a complete response takes several seconds, users often prefer to see partial results immediately rather than waiting for the entire output.

The psychological impact of streaming is significant and measurable. User studies show that perceived response time for a 3-second generation with immediate streaming feels similar to a 1.5-second generation without streaming. However, implementing streaming correctly is more complex than simply sending tokens as they arrive.

Token streaming addresses this by sending generated tokens to the client as soon as they’re produced, creating a typewriter effect that provides immediate feedback. This approach requires careful implementation to handle network buffering, error conditions, and client-side rendering efficiently.

The implementation typically uses Server-Sent Events (SSE) or WebSocket connections to maintain a persistent communication channel between the server and client. Each generated token is immediately serialized and transmitted, along with metadata indicating the current generation state and any confidence scores or alternative candidates.

Network buffering can sabotage streaming implementations. TCP’s Nagle algorithm and various proxy servers often buffer small packets, introducing 40-200ms delays that defeat the purpose of streaming. Production systems must explicitly disable Nagle’s algorithm and use HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 where possible to minimize buffering delays. Additionally, reverse proxies like nginx require specific configuration (proxy_buffering off) to avoid accumulating streamed responses.

Browser compatibility introduces another layer of complexity. While modern browsers handle SSE well, older versions or certain corporate firewalls can interfere with streaming connections. Production systems typically implement fallback mechanisms that detect when streaming fails and switch to traditional request-response patterns.

Streaming becomes more complex when dealing with constrained generation scenarios, such as JSON output or structured data formats. The system must buffer tokens until it can verify that the partial output remains valid according to the specified constraints. This might require implementing streaming parsers that can validate partial structures and provide early termination if the generation goes off-track.

For JSON generation, you can’t stream individual characters because partial JSON is invalid. Instead, the system must buffer until complete JSON objects or arrays are formed. This reduces the streaming benefit but still provides better user experience than waiting for complete responses. The buffering strategy might hold tokens until reaching closing braces or brackets that complete valid JSON fragments.

Error handling in streaming scenarios requires special consideration. If generation fails midway through a response, the client needs to be notified appropriately, and any partial results must be clearly marked as incomplete. Recovery strategies might include automatic retry with different sampling parameters or fallback to alternative models.

The infrastructure costs of streaming are also significant. Each streaming connection maintains server resources for the entire generation duration, typically 2-10 seconds per request. For high-volume applications, this can require 5-10x more connection handling capacity compared to traditional request-response patterns. Load balancers must be configured to handle long-lived connections, and connection pooling strategies need adjustment.

Asynchronous Queue Management and Backpressure Control

Production inference systems must handle highly variable request loads without degrading performance or dropping requests. A robust queueing system serves as the buffer between unpredictable user demand and the fixed computational capacity of the inference hardware.

The challenge becomes apparent during traffic spikes. A typical production system might handle 100 requests per minute during normal operation, but see spikes to 1000 requests per minute during peak usage or viral events. Without proper queueing, these spikes either crash the system or force you to overprovision hardware by 10x to handle rare peaks.

Asynchronous queues decouple request reception from processing, allowing the system to accept requests even when all compute resources are busy. The queue management system must implement multiple priority levels, timeout handling, and fair scheduling policies to ensure good user experience across different usage patterns.

The queue depth becomes a critical operational metric. In practice, queue depths of 50-100 requests are manageable, but beyond 200-300 requests, user experience degrades significantly. Users expect responses within 10-15 seconds for interactive applications, so queue depths translate directly to response time guarantees. A queue processing 10 requests per minute with 200 pending requests means 20-minute response times, which is unacceptable.

Backpressure mechanisms prevent the system from accepting more work than it can handle, which could lead to cascading failures or excessive latency. When queue depth exceeds predetermined thresholds, the system can implement various strategies: rejecting new requests with appropriate error codes, upgrading to faster but less accurate models, or redirecting traffic to alternative endpoints.

The implementation often involves multiple queue tiers with different service level agreements. Premium users might have access to a high-priority queue with guaranteed sub-5-second response times, while free tier users accept longer delays. The scheduler must balance these priorities while avoiding starvation of lower-priority requests.

Redis Streams or Apache Kafka provide robust foundations for distributed queueing, but the integration with GPU inference workers requires careful consideration. GPU workers can’t efficiently handle traditional message acknowledgment patterns because they need to commit to processing requests for several seconds. Dead letter queues become essential for handling requests that fail processing or exceed timeout limits.

The queue management system should implement sophisticated timeout handling that considers both user expectations and resource utilization. Short requests might have tight timeout requirements, while complex analytical tasks might warrant longer processing windows. The system must track per-request timeouts and proactively cancel work that can no longer meet its deadline.

Circuit breaker patterns add another layer of protection. If the inference service starts returning errors at rates above 5-10%, the circuit breaker can redirect traffic to fallback responses or cached results rather than continuing to queue requests that will likely fail. The circuit breaker must distinguish between temporary GPU memory pressure and permanent model failures to avoid unnecessary service degradation.

Priority-based scheduling allows the system to differentiate between different types of requests. Interactive user queries might receive higher priority than batch processing tasks, or premium users might get preferential treatment during high-load periods. However, implementing fairness across priority levels requires careful tuning to prevent lower-priority requests from being starved indefinitely.

Hardware-Aware Runtime Optimization

Modern inference acceleration relies heavily on specialized hardware features and optimized software stacks that can take advantage of these capabilities. Graphics processors offer tensor cores designed specifically for mixed-precision arithmetic, while newer architectures provide dedicated units for sparse computations and quantized operations.

The gap between theoretical performance and actual throughput can be startling. An A100 GPU advertises 312 TFLOPS of mixed-precision performance, but naive PyTorch implementations often achieve only 20-40 TFLOPS in practice. The difference lies in memory bandwidth utilization, kernel fusion, and precision management that specialized runtimes handle automatically.

TensorRT, NVIDIA’s inference optimization library, provides automatic kernel fusion, precision calibration, and memory layout optimization specifically tuned for inference workloads. The system analyzes the computational graph and applies various optimizations: fusing consecutive operations to reduce memory bandwidth requirements, selecting optimal precision levels for different operations, and choosing memory layouts that maximize cache efficiency.

In production deployments, TensorRT can improve inference speed by 2-5x compared to standard PyTorch implementations, but the optimization process itself can take 10-30 minutes depending on model size. This optimization time must be factored into deployment pipelines, and the optimized models are hardware-specific and can’t be easily moved between different GPU architectures.

The precision calibration process requires representative data samples to determine optimal quantization scales. Using inappropriate calibration data can result in accuracy degradation that might not be immediately apparent in automated tests but becomes obvious in production usage. The calibration dataset should represent real user inputs, not just validation sets from model training.

ONNX Runtime offers cross-platform optimization capabilities that can target different hardware backends while providing a unified interface. The runtime includes optimization passes that eliminate redundant operations, fold constants, and apply algebraic simplifications that reduce computational requirements without affecting model accuracy.

However, ONNX conversion introduces its own challenges. Complex PyTorch operations might not have direct ONNX equivalents, requiring manual implementation of custom operators. The conversion process can also introduce subtle numerical differences that accumulate over long generation sequences, leading to different outputs compared to the original PyTorch model.

For CPU-based deployment, specialized runtimes like llama.cpp implement highly optimized kernels that take advantage of specific instruction sets such as AVX-512 or ARM NEON. These implementations often outperform general-purpose frameworks by significant margins, especially for quantized models running on consumer hardware.

The performance characteristics vary dramatically across hardware. A quantized INT8 model might run 3x faster on modern Intel CPUs with VNNI instructions, but show minimal improvement on older architectures lacking these specialized units. Apple’s M-series processors with their unified memory architecture demonstrate different optimization patterns entirely, often favoring larger batch sizes than traditional GPU deployments.

The choice of runtime significantly impacts performance, and the optimal selection depends on the specific model architecture, target hardware, and precision requirements. A quantized INT8 model running on a runtime optimized for full-precision operations might perform worse than the original FP32 model on a properly optimized stack.

Framework overhead becomes particularly visible in high-throughput scenarios. Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) can become a bottleneck when handling many concurrent requests, even if the actual model inference happens in optimized C++ or CUDA code. Production systems often use multiple worker processes or specialized serving frameworks like Triton Inference Server to bypass these limitations.

Fault Isolation and System Resilience

Large language models are complex systems that can fail in numerous ways: memory leaks that gradually degrade performance, infinite loops in generation that consume resources indefinitely, or edge cases in input processing that cause crashes. Production systems must be designed to contain these failures and maintain overall service availability.

The failure modes are often subtle and difficult to detect in development environments. Memory leaks might only become apparent after processing thousands of requests over several hours. A model might work perfectly for 99% of inputs but crash on specific Unicode characters or extremely long input sequences. These edge cases are particularly problematic because they can bring down entire model instances, affecting many concurrent users.

Process isolation provides the fundamental building block for fault tolerance by running each model instance in a separate process or container. When a model process crashes or becomes unresponsive, only that specific instance is affected, and the orchestration system can restart it without impacting other running models or user sessions.

In practice, containerization with Docker or similar technologies provides the necessary isolation, but the configuration details matter significantly. Memory limits must be set appropriately to prevent one model from consuming all available system memory, but too-restrictive limits can cause legitimate requests to fail. GPU memory isolation is particularly challenging because CUDA contexts are typically shared across processes on the same device.

Kubernetes provides excellent orchestration capabilities for containerized model serving, but the default restart policies aren’t always appropriate for GPU workloads. A crashed model container might restart on a different node that doesn’t have the required GPU resources, leading to extended downtime while the scheduler finds appropriate placement.

Health monitoring systems continuously probe model instances to detect degraded performance or unresponsive behavior. These checks might include periodic test queries with known expected outputs, memory usage monitoring, and response time tracking. When an instance fails health checks, it can be automatically removed from the serving pool and restarted.

The health check implementation requires careful consideration of what constitutes a failure. A model that takes 30 seconds to respond to a complex query might be functioning normally, but a model that takes 30 seconds for a simple “hello world” request is clearly degraded. The health checks must distinguish between temporary load-induced slowdowns and permanent failures.

Memory leak detection becomes crucial for long-running model services. GPU memory leaks are particularly insidious because they might not be immediately apparent and can gradually degrade performance over hours or days. Monitoring GPU memory usage patterns and implementing automatic restarts when memory usage exceeds expected thresholds helps maintain system stability.

Hot restart capabilities allow the system to replace failed model instances without service interruption. This requires maintaining warm standby processes that are ready to accept traffic immediately when a primary instance fails. The standby processes must have the model already loaded in memory and be prepared to handle the specific configuration and routing requirements of the failed instance.

The cost of maintaining hot standbys is significant, potentially doubling infrastructure costs. More economical approaches might maintain cold standbys that can be activated within 30-60 seconds, accepting brief service degradation in exchange for lower operational costs.

Circuit breaker patterns protect the overall system from cascading failures when individual components become unreliable. If a particular model endpoint starts returning errors at a high rate, the circuit breaker can temporarily stop routing requests to that endpoint, allowing it time to recover while protecting users from experiencing failures.

The circuit breaker configuration requires tuning based on expected failure patterns. A threshold of 10% error rate might be appropriate for experimental models, while production-critical services might use 1-2% thresholds. The recovery time must balance system stability with service availability, typically using exponential backoff to gradually reintroduce traffic to recovered endpoints.

GPU-Aware Autoscaling Strategies

Traditional autoscaling approaches based on CPU metrics are inadequate for GPU-accelerated inference workloads where the primary constraint is specialized compute resources rather than general processing capacity. Effective autoscaling for language model inference requires metrics that reflect GPU utilization, memory pressure, and queue dynamics.

The challenge is that GPU metrics are fundamentally different from CPU metrics. While CPU utilization is relatively uniform and predictable, GPU utilization can spike from 0% to 100% within milliseconds as batch processing begins and ends. A GPU showing 30% average utilization might actually be alternating between 0% idle and 100% busy states, making traditional threshold-based autoscaling ineffective.

GPU memory utilization provides a critical signal for scaling decisions, but it must be interpreted carefully. Unlike CPU memory, GPU memory is typically allocated in large chunks and managed differently by various frameworks. The autoscaler must distinguish between memory that’s allocated but idle and memory that’s actively being used for computation.

In practice, monitoring GPU memory fragmentation becomes as important as monitoring total usage. A GPU showing 60% memory utilization might actually be unable to accept new requests due to fragmentation, necessitating scale-out decisions based on memory fragmentation metrics rather than just total usage.

Request queue length and processing latency offer additional signals that reflect user-visible performance degradation. When average response times start increasing or queue depths grow beyond acceptable thresholds, the system should proactively scale out additional capacity rather than waiting for resource exhaustion.

Cold start considerations become particularly important for GPU workloads where model loading can take 30-60 seconds or more. The autoscaler must anticipate demand increases and begin warming new instances before they’re critically needed. This might involve maintaining a small pool of pre-warmed instances or implementing predictive scaling based on historical usage patterns.

The autoscaling system must also consider the heterogeneous nature of GPU resources. Different instance types offer different capabilities, and the system might need to choose between adding high-memory instances for long-context workloads versus high-throughput instances for many short requests.

Token Budget Management and Output Control

Inference costs scale directly with the number of tokens processed, including both input context and generated output. Production systems require sophisticated controls to manage these costs while maintaining good user experience across different usage tiers and application requirements.

Token budgeting operates at multiple levels: per-request limits that prevent individual queries from consuming excessive resources, per-user quotas that enforce fair usage policies, and system-wide controls that protect against resource exhaustion during traffic spikes.

The implementation must distinguish between different types of token usage. Input tokens consumed by long documents or conversation history might be treated differently from output tokens generated in response to user queries. Some applications might allow unlimited input processing but strictly control output generation, while others might implement combined budgets.

Early stopping mechanisms provide additional cost control by terminating generation when certain conditions are met. This might include stopping at natural sentence boundaries, detecting repetitive outputs, or identifying when the model’s confidence in subsequent tokens drops below acceptable thresholds.

Rate limiting complements token budgeting by controlling the temporal distribution of resource usage. A user might have a large token budget but be limited in how quickly they can consume it, preventing burst usage patterns that could impact other users or destabilize the system.

Comprehensive Observability and Performance Monitoring

Effective optimization requires detailed visibility into system behavior at multiple levels: individual request performance, model-level metrics, hardware utilization, and overall system health. The monitoring system must capture both real-time operational data and longer-term trends that inform capacity planning and optimization priorities.

Request-level telemetry tracks the complete lifecycle of each inference request: queuing time, model loading time, actual inference duration, and response transmission time. This granular data enables identification of bottlenecks and optimization opportunities that might not be visible in aggregate metrics.

GPU profiling provides insights into hardware utilization patterns, memory access efficiency, and kernel performance. Tools like NVIDIA Nsight or PyTorch Profiler can reveal whether computational kernels are memory-bound or compute-bound, informing decisions about model architecture changes or runtime optimizations.

Cache performance metrics become particularly important for systems using KV caching or other memory optimization techniques. Cache hit rates, memory fragmentation levels, and eviction patterns provide insights into how well the caching strategy matches actual usage patterns.

Distributed tracing becomes essential for complex multi-GPU or multi-model deployments where a single user request might involve multiple service components. The tracing system must correlate activities across different processes and devices to provide a complete picture of request processing.

The monitoring system should implement automated alerting that can detect both immediate failures and gradual performance degradation. This includes not just binary up/down checks, but also trend analysis that can identify slowly developing problems before they impact users.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: